Sometimes it can take a while before the Zeitgeist catches up with the thinking, sensibilities, and achievements of certain artists who, despite challenges, setbacks, and the changing currents of the always fickle art establishment, somehow manage to stay true to their own ways of observing the world as they develop their art-making techniques and express their distinctive personal visions.

When they’re not overlooked — or perhaps more dispiritingly, ignored — they may still find it hard to attract attention to their efforts due to a multitude of factors, including an inability to or a lack of enthusiasm for playing the art world’s prescribed self-promotion game.

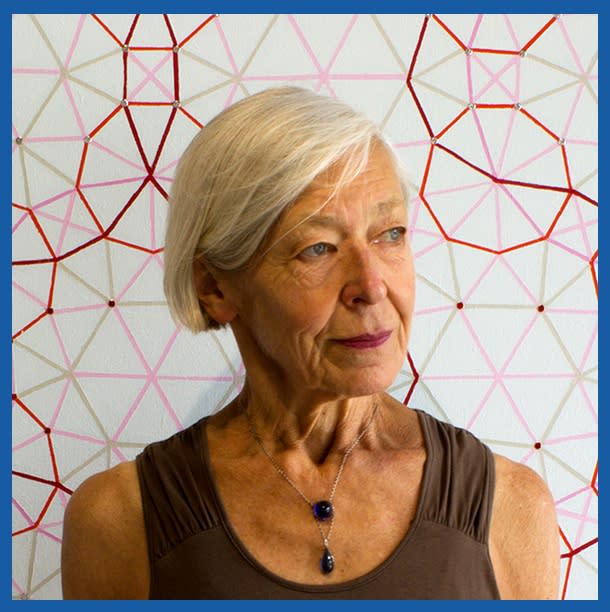

Like their creator, the diverse series of works that made up the wider, multifaceted oeuvre of the Lithuanian-born, American artist Audra Skuodas (1940-2019) wore no easy art-market labels.

In this way, along with the fact that, for many decades, Skuodas lived and worked in the college town of Oberlin, Ohio, far enough away from such art-market centers as Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles to find it challenging to penetrate them from a distance, she became an artist who was able to pour her energy, with a strong sense of focus, into her work — and immerse herself in the creative process, with gusto and an abiding sense of wonder at its cathartic power, which is just what she did.

“Even as a child, my mother was always making things — paintings, drawings, and paper dolls; she was very inquisitive and, in high school, won awards,” her daughter, the artist and jewelry designer Cadence Pearson Lane, recalled in a recent video-call interview with brutjournal. We spoke with her on the occasion of the presentation of “Vibrational Vulnerability,” an exhibition of a selection of Skuodas’s abstract and figurative paintings, works on paper, and drawings incorporating the stitching of embroidery thread that is on view at Cristin Tierney Gallery in New York (October 25, 2024 through January 17, 2025). It’s the first New York gallery showing of the late artist’s work in over 15 years.

Skuodas was born in Lithuania in 1940; she immigrated with her family — both of her parents had been university professors — to the United States when she was ten years old after having spent seven years in a displaced-persons camp in the former West Germany. In the U.S., the Skuodas family settled in Illinois, where Audra went on to study art at Northern Illinois University in Dekalb.

Later, she taught, in Canada, at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, a school that became a locus for emerging ideas about what would become known as conceptual art. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Skuodas was starting her professional career as an artist, pop art’s heyday was behind it, minimalist art was articulating a new aesthetic, and the political, social, and aesthetic critiques that informed what would become known as feminist art were in the air.

After her teaching stint in Canada, Skoudas pulled back into the private world of her home and studio, where she philosophically explored art-making, motherhood, and the nature of many aspects of everyday life. She amassed a large personal library and, as a self-described spiritual seeker on an unsinkable, perennial quest for understanding of the forces that shape and control the natural world, human relations, history, and a possible, broader, universal collective consciousness, she read extensively in such subject areas as philosophy, psychology, spirituality, art history, and social science. As a researcher-explorer, a mother, and an artist, she was intrigued by what it was that made the world — and the people and other life forms in it — tick.

Skuodas was aware that there were a lot of overlapping ideas and energies packed into her artworks, even though, after an early phase of painting mostly representationally in the service of her philosophical themes, her art became spare and abstract. It was marked by geometric compositions humming with implied, if indecipherable, symbolic meanings, and gentle palettes whose light, pastel colors appeared to be tethered to their canvases or paper support surfaces only tentatively, like so many drifting expanses of colored air.

As an art student at Northern Illinois University, Skuodas began using light blues and pinks to make her paintings. At that time, however, as Cadence Pearson Lane recalled her mother having told her, “One of her art teachers informed her that she must not use light blue and pink; he said they were not serious colors and that using them went against the rules of painting. One night, this same professor went into the students’ studio and painted over all of my mother’s canvases with black paint.” Later, light blue and pink became signature colors in many of Skuodas’s mature works.

It was at Northern Illinois University that Skuodas met the sculptor John Pearson, who came from Yorkshire, in northern England, and whom she later married. The artists eventually moved to Oberlin, Ohio, where Pearson became a teacher in Oberlin College’s art department, and the couple bought a former, multi-floor furniture-store building on the town’s main street, which they transformed into a home, with art studios.

In an artist’s statement written in the 1980s, Skuodas observed, “My work does not have a specific, directed meaning.” About her working method, she noted, “Although there appears in my painting a calculated, premeditated, and logical quality in terms of image and organization, this belies the[ir] true means of execution. [Each] painting is initiated because of a chance encounter with a personally — to me — appealing image, be it [that of] a person, [or] a photograph of a person, flower, or other image. In a sense, I spend days looking for the right image upon which to build a fantasy.”

Skuodas was keenly aware that viewers of her works were eager to know exactly what messages they — and their creator — might have intended to convey, but for the artist, apparently, their ambiguity or open-endedness may well have been their point, especially considering that she seemed to recognize her artistic productions as the by-products and evidence of her own search for understanding with regard to that enduring, unfathomable subject of spiritual seekers everywhere — the meaning of existence itself.

In her artist’s statement, Skuodas wrote, “There seems to be a strong need on the part of the viewer to discover [my] symbolic or psychological intentions. Although I know there are hidden implications and symbols [in my work], I am never fully conscious of their specific meaning[s]. I do intend the paintings to contain certain ‘essential’ psychological tensions but [I] try to allow this to ‘happen,’ thereby reaching a subliminally unknown realm of myself. Because of the speed of execution and my total absorption in the process, when I stand back to contemplate [a] painting, I am often surprised at the resultant juxtapositions.”

Over the years, Skuodas often produced thematically related groups of artworks. Her series bear such titles as “Broken Melodies – Discordant Fragments,” “Sensitization – Desensitization,” “Vibrational Vulnerability,” and “Energy Patterns.”

Lisa Kurzner is the founder and director of the Abattoir Gallery in Cleveland, Ohio, which represents Audra Skuodas’s artistic estate and is now working in collaboration with the dealer Cristin Tierney of New York’s Cristin Tierney Gallery to present and promote the late artist’s paintings, works on paper, and mixed-media objects. Those mixed-media creations include Skuodas’s handcrafted books, each of which is unique and gives intimate-feeling form to her syntheses of her thoughts and findings about the subjects that intrigued her.

Kurzner told brutjournal, “I was aware of Audra and had met her and John Pearson after moving to Ohio in 2009. I was an independent curator in Cleveland and the curator of the first FRONT International/Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art in 2018. I established my gallery in Cleveland in 2020, and John Pearson was the second artist whose work I showed. Years later, in the 2020 FRONT Triennial, I saw one of Audra’s paintings. By that time, she had recently passed away, but I was so moved by that painting that I called Cadence and said, ‘We’ve got to talk.’”

As Cadence Pearson Lane pointed out, for a long time, in her earlier, one-of-kind artist’s books, Skuodas tended to bring together quotations from philosophers and historical figures with her stylized images. When their contents are not completely abstract, they may feature long-limbed, naked human figures that often stretch or float in their airy pictorial space like characters in unfolding, unknown narratives. In her later artist’s books, Skuodas found the confidence to write her own philosophical observations about the subjects that seized her imagination; she no longer needed to illustrate other thinkers’ statements or to reinforce or match her images with their borrowed, quoted words.

The current exhibition in New York offers viewers who are not familiar with Skuodas’s career and the range of media and genres in which she worked an introduction to her art and, notably, a vivid sense of the manner in which one artist employed both the fundamentals of figurative drawing and, on her own terms, in her own way, the language of modernist abstraction to give tangible form to the ineffable.

Were Audra Skuodas’s art and her decades-long search for understanding of the human condition in the contexts of history and what she sensed to be inexplicable, eternal, universal forces a response to an early childhood experienced against a backdrop of war?

Could it be that her sometimes tranquil, sometimes edgy compositions may be seen, simultaneously, as both the expression of the questions that motivated her spiritual quest and as the mysterious field reports she brought back from her forays into the farthest reaches of that other universe — the one that lies somewhere in the unknowable depths of the human soul?

In notes about her work written in 2015, Skuodas observed that her art may be seen as what she called “a distillation of energies, reverberations, responses, [and] echoes.” She was interested, she added, in “[s]ensitive chaos formulating itself into waves, patterns, and natures intermeshing,” and in the “parallel phenomena” of the body and the spirit.

Now, perhaps unexpectedly, something about Skuodas’s work feels timely and insightful. Today, with political and corporate corruption; hate, hostility, violence, and war-making; injustice and suffering; and humankind’s thoughtless destruction of the natural environment running rampant just about everywhere, Skuodas’s attempt to make sense, through art, of just about everything may feel more audacious, ambitious, and relevant than ever.

Visit the website.